The Last Speaker on Earth

You may not generally think about how many people speak your language unless you find yourself in a situation where you’re surrounded by people who speak a different language than your own. Whether it be in the middle of a market in Jaipur, or arguing with a tuk tuk driver in Phnom Penh, you start to realize how isolated you are. Imagine if that was your daily life, as opposed to just an experience you may have had once or twice. How crazy would it feel if you were one of only a handful of people who spoke and understood one particular language?

It turns out that there is currently only one person in the world left who can speak the Native Amazonian language of Resígaro. His name is Pablo Andrade Ocagane and he’s 65 years old. His sister, Rosa, was murdered, leaving him to be the only surviving speaker of the language. Not only that, but he is one of the last 40 people living to be able to speak Ocaina, another Native Amazonian language.

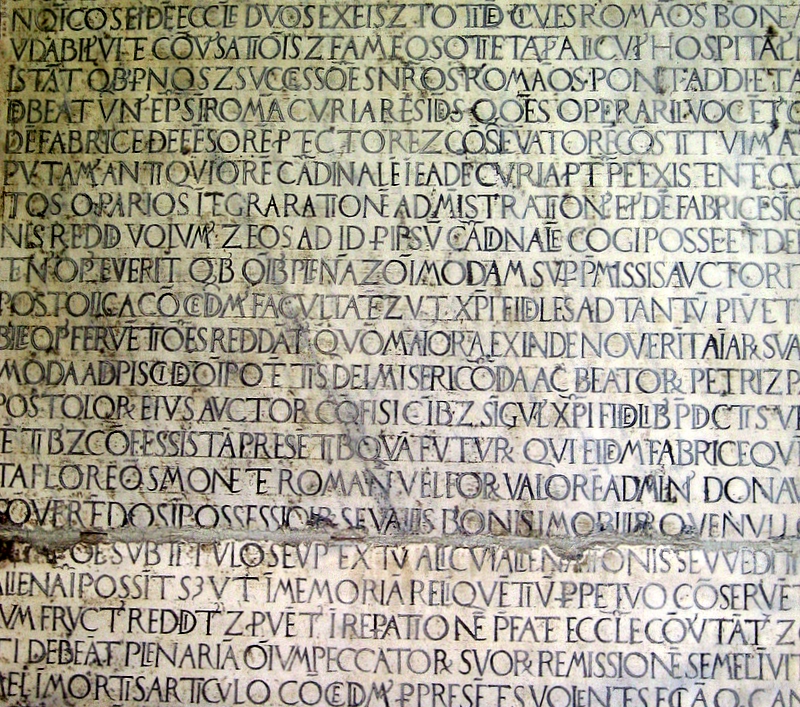

Photo via Flickr

The Death of a Language

Some languages die out and lose popularity with modern populations, causing them to become less and less frequently spoken, learned or understood. Look at Latin. Latin used to be taught in schools all over the Western world and was the official language of scholars and the educated elite. Many Catholic masses were held in Latin right up until as late as the 1970s―some churches still hold mass in Latin, but the chances of you having a conversation in Latin outside of a Classic’s classroom are virtually non-existent.

However in the case of Resígaro, it’s not about a dwindle in popularity, but more about the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. Much like the Amazon rainforest has decreased in size due to deforestation, it’s indigenous people and by proxy it’s indigenous languages are also losing ground. The Amazon basin countries hold almost 20% of all the endangered languages in the world. Languages like Japeria, Macushi, or Panare―a language with only 3000-4000 speakers. European colonists from Portugal and Spain are a big reason as to why these languages died out initially, though the rapid decline in Native Amazonian languages has a lot to do with deforestation. Nearly 30 languages that once existed within the Amazonian basin are now generally thought to be extinct, with 400 or more in danger of the same fate.

Photo via Flickr

Moments of Existentialism

What are we to do in situations such as these? When we we lose a language, we lose the culture and the identity that comes with it. It might seem impossible to consider living in a world where you are in the same position as Pablo Andrade Ocagane, where a language and a cultural rest in your hands to protect and share with the world. How would you go about maintaining linguistic integrity, when you may no nothing at all about teaching your language to others, or what might have been considered important in your linguistic culture outside of what you, personal, valued?

The Peruvian government has been attempting to rescue indigenous languages and linguistic knowledge and are working with Pablo to revise a Resígaro dictionary and grammar book, to ensure that the language is preserved in some way. The project began in the 1950s with Pablo’s siblings but now remains a task that only he, alone, can complete.

Many Indigenous Canadian languages face a similar fate, with languages like Onandaga, Seneca, and Abenaki having less than 100 speakers left. This is not simply an Amazonian problem, as most Australian aboriginal languages have fewer than 1000 speakers, and countries like France experiencing a rapid decline in speakers of languages like Basque, Catalan, Corsican, and West Flemish.

In Conclusion

When we lose a language, we lose a cultural identity and a part of history. It’s a sad thought to imagine many native or indigenous languages disappearing as globalisation, deforestation and human migration takes its toll on world. Knowing that these languages exist and doing our part to keep the people that speak them sharing that knowledge with further generations, as well as encouraging governments to hold cultural diversity; and Aboriginal peoples, their culture and their land, in higher regard is a huge step to help prevent further language and culture loss. The more you know about an issue, the better prepared you can be to fight it.

What could you do to help people like Pablo continue to preserve their language and culture?