Dyslexia and Learning a Foreign Language

Dyslexia as defined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke is “difficulty with phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), spelling, and/or rapid visual-verbal responding. Individuals typically read at levels significantly lower than expected despite having normal intelligence.” Approximately 10-15 percent of English speakers deal with dyslexia on some level “affecting over 40 million American children and men.”

What with this being a language-based disability, have you ever wondered how it would work if you add more language into the mix? If you’re dyslexic in one language, could you be dyslexic in both? Science hasn’t completely come to the rescue yet, but while the probability is high that the same disability may persist, it may not manifest in exactly the same way and potentially even result in benefits in English. Take a look as we try and answer whether dyslexia can traverse in learning another language.

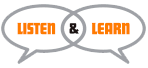

Human Brain via Wikimedia

The meaning of science

First of all, science hasn’t come to a consensus about the condition. Dyslexia is an umbrella term covering a wide range of reading disabilities and cognitive disorders. Among English-speakers it is generally considered a phonological disorder—or the degree of inability to organize and recall specific, individual sounds to corresponding syllables or words (i.e. phonemes and graphemes). Dyslexics get tangled up in the reading process when they are forced to connect the phonics—or specific utterances associated with written letters or groups of letters—to the phonemes.

Over the years, research has established that dyslexia involves both genetic and environmental factors which affect reduced activation of the left temporal lobe – the part of the brain tasked with processing visual and audible information (aka Broca’s area). Studies also show similar brain abnormalities between nationalities, which means dyslexics in China suffer from roughly the same condition as those in Italy. However, Italians are about a third less likely to exhibit dyslexia as their Chinese counterparts, and reported cases in Italy have only half the incidence found in the United States.

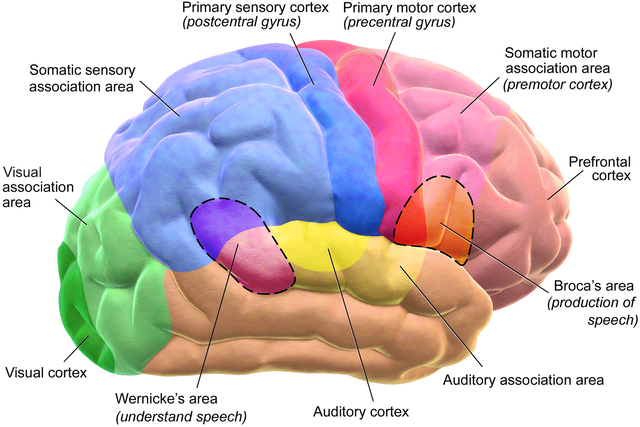

Indo-European Languages via Wikimedia

Language Mechanics

In order to understand the dyslexic differences (and similarities) between languages, you have to look much deeper into the mechanisms associated with reading and speaking, and something called orthography. Writing systems offer basic but consistent variations in writing-language relationships. Orthographies, on the other hand, reflect the complexity, consistency, or transparency of the grapheme-to-sound correspondence.

To make a long story short, English, French, Hebrew and Chinese are considered opaque and contextually “deep”; whereas Spanish and Italian are transparent and orthographically “shallow” languages with fewer variations in their grapheme-to-sound correspondence.

Thus, in the realm of language learning and dyslexia, some languages may be more sympathetic than others. For example, though Italian shares an alphabet with the majority of Indo-European languages and writing systems, the letter-to-sound relationship is vastly more consistent than French and English. Italian is that “shallow” language: whenever you see the ‘ch’ combination, it’s going to make the same sound. Whereas in English, the same ‘ch’ combination could have a number of pronunciations (c.g. the difference between chorus, chuck, Chicago, and chandelier; bench and architect.).

Language Possibilities

Now, a common misunderstanding is that dyslexia boils down to a mismatch of letters vs. sounds, which might indicate you could be dyslexic in one language not the other; specifically, in languages and writing systems that utilize ideograms rather than letters, e.g. Chinese and Japanese. However, using visual and audio tests, as well as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans, researchers from the University of Hong Kong determined that while dyslexia in English-speakers is primarily due to a sound-related processing problem, among Chinese speakers, it is likely driven by both visual and sound processing disorders.

In response to the University of Hong Kong study, a pair of British neuroscientists argued it’s possible to be dyslexic in English but completely normal in a language such as Japanese. They think dyslexia universally affects “phonemic analysis” – the ability to convert letters into sounds, which the reader then assembles into syllables, words, and eventually, complete thoughts. They suggest that the phonemic-analysis theory also explains why there are fewer Chinese dyslexics: phonemic analysis is extraneous for Chinese readers. However, as the Hong Kong study suggests, Chinese dyslexics seem to have a problem in an entirely different part of the brain from English dyslexics.

Whereas English readers can use letters to sound words out, pronunciation of specific characters in Chinese languages is dependent on rote memorization, i.e. knowing which character’s pronunciation to access is dependent on a thorough understanding of the complex combination of strokes included in each character. Chinese characters contain both semantic (meaning) information and phonological information. The phonological information not related to the syllable but the character. Thus, learning to read and write Chinese is therefore a very different process.

Photo via Flickr

Of course, none of this is set in stone. The science of dyslexia continues to evolve. Very broadly, in languages with shallow orthographies (e.g., Finnish, Spanish, and Turkish), phonology predetermined in print; therefore, these languages are easier to learn. On the other hand, in deep orthographies (e.g., English, French, and Hebrew), there is a complex relationship between graphemes and phonemes, with more ambiguity leading to greater difficulty learning to read words.